Good morning! It’s Wednesday, and here are this week’s five items for you.

1. A take I haven’t written elsewhere

American parents want a phone-based childhood

In a Monday column engaging the Haidt book, New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg begins by noting that the “alarm over what social media is doing to kids is broad and bipartisan.” She has found herself, on this point, in agreement with officials as politically distant as New York Attorney General Letitia James, who brought the civil fraud lawsuit against former President Donald Trump, and Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), noted Trump sycophant.

Haidt, says Goldberg, is “pushing on an open door” with this book, and she “suspect[s] that many readers won’t need convincing” of his thesis.

I’m not so optimistic. Or rather, I think she’s right at one level and wrong at another. She’s right that it is increasingly fashionable to talk about the risk phones pose to American kids, especially teenage girls. The dysfunction of the phone-based childhood has become impossible to ignore, thanks in no small part to Haidt’s own work. We’re all saying it: Make the kids put down their phones at dinner! Ban phones in school! Kick teenagers off social media or confine them to flip phones or take the phones away altogether!

But then there’s the second level: When push comes to shove, whatever ideals they may spout about rejecting the phone-based childhood, average American parents want their middle and high schoolers to have phones, preferably smartphones with location tracking kept on their persons at all times.

Goldberg briefly gestures in this direction. “Phone-free schools are an obvious start,” she writes, “although, in a perverse American twist, some parents object to them because they want to be able to reach their kids if there’s a mass shooting.” A few lines later, she acknowledges that “parental fear” is a cause of the decline of childhood freedom and play.

This is true, but I’m not sure it gets at the extent of the parent problem.

A recent poll commissioned by the National Parents Union, an advocacy group focused on public schools, paints a fuller picture and backs up my sense on this. Respondents were parents of public school students in K-12:

When it comes to cell phones in school, parents lack trust in having schools keep phones away from their children during the day. 43 percent of parents say their child’s school bans cell phone use unless they have a medical condition for which it is needed, but only 32 percent support this policy. The majority of parents (56 percent) believe students should sometimes be allowed to use their cell phones in school, during times like lunch or recess, at athletic events and in class for academic purposes approved by their teacher. [margin of error +/- 2.9 percent, emphasis mine]

In 2024, summarized the organization’s president, “all families rely on cell phones to stay connected and communicate,” and “parents want to be able to have clear and open channels of communication with their own children. Banning cell phones outright in school or treating them like contraband,” she concluded, “is entirely unreasonable and not grounded in the reality we will live in.”

I think that’s absolutely nuts—but the poll results suggest she’s representing her constituents well. Functionally, American parents want a phone-based childhood for their kids, or at least they want it more than the alternative because they so highly value the safety and intimacy they believe it provides.

Getting into the poll toplines, we find that 60 percent of these parents first allowed their children to have cell phones between the ages of 10 and 13. Another 29 percent permitted it at age 9 or younger. Waiting until 15 or 16, the standard ages for driver’s licenses and work permits, is almost unheard of.

These parents overwhelmingly report believing their child’s phone has a positive (46 percent) or net neutral (42 percent) effect. And of those whose children take a phone to school, eight in 10 parents said they want this to happen “so that [their] child can use their phone if there is an emergency at school” and seven in 10 want it “so that [they] can get in touch with [their] child or find out where they are when needed.”

So yeah, there’s an open door for Haidt’s book. But it’s generally not a door to the homes of people actively parenting teenagers.

In my observation, enthusiasm for taking away children’s smartphones and making kids touch grass is running high—in demographics including free-range childhood libertarians, journalists, social scientists, pastors, doctors, some teachers, DINKs, grandstanding politicians, social media execs when they need to look contrite in public, select high schoolers who Read Serious Literature, and nostalgic grandparents who are not involved in coordinating the grandkids’ weekly schedules.

And look, as a free-range childhood libertarian and journalist (and an erstwhile Serious Literature high schooler), I share that enthusiasm. But I strongly doubt most of the actual decision-makers—parents of tweens and teens—are with us on this.

Lotta lip service, sure. Lotta worrying that the youths aren’t independent and responsible anymore. But in practice, data and anecdote alike suggest to me that fear is winning. “Parents are fed up with what childhood has become,” Haidt writes at the end of the Atlantic excerpt. I believe that’s true of too few, and I hope his book changes the relevant minds.

2. What I'm reading this week

“Laboring in the dark,” by Charlotte Collingwood (a pseudonym) for The New Atlantis. It’s an interesting, well done, and sympathetic piece on IVF which New Atlantis editor Ari Schulman said “unsettled [his] own views in ways [he’s] still working out.” I understand that response but found the article, in the end, frustrating in the way that much of this conversation is frustrating: It does not attend to the exact ethical concern the average Protestant IVF critic raises.

From what I’ve seen, this is typically not the Catholic objection about how procreation ought to work (for the gist of that, see the paragraph beginning “This leads to the other major criticism of IVF” here). It’s about what happens to any embryos that successfully develop but aren’t transferred into the womb: Are they rejected at random or because of sex selection or genetic testing? Are they left frozen indefinitely? Could they be adopted? Will they be discarded or donate for research? (In this New Atlantis story, every embryo that develops is transferred—just two—so we don’t know what the author would have done with extras.)

The fate of such embryos is central to the Alabama court case that kicked off this whole controversy, and it’s central to many Protestants’ ethical qualms about IVF, which don’t necessarily concern the process as a whole. So why isn’t it named and narrowly considered in so many IVF conversations?

3. A recommendation

Make some Italian cream soda at home. It’s very easy:

ice

unflavored fizzy water of choice

half and half

sweetening syrup and flavor of choice (maybe one and the same)

The ratios can be to your taste; I probably land somewhere around nine ounces of water to a little over one ounce of half and half and a bit under an ounce of syrup. Often I use maple syrup, because it’s easy, but if you have it on hand, simple syrup with a little vanilla and/or almond extract is a good option, too. I find my brain wants to categorize the resulting concoction as “milkshake,” even though it’s mostly water.

4. Recent work

What Ukraine needs instead of NATO | Defense Priorities (newsletter)

5. Miscellaneous

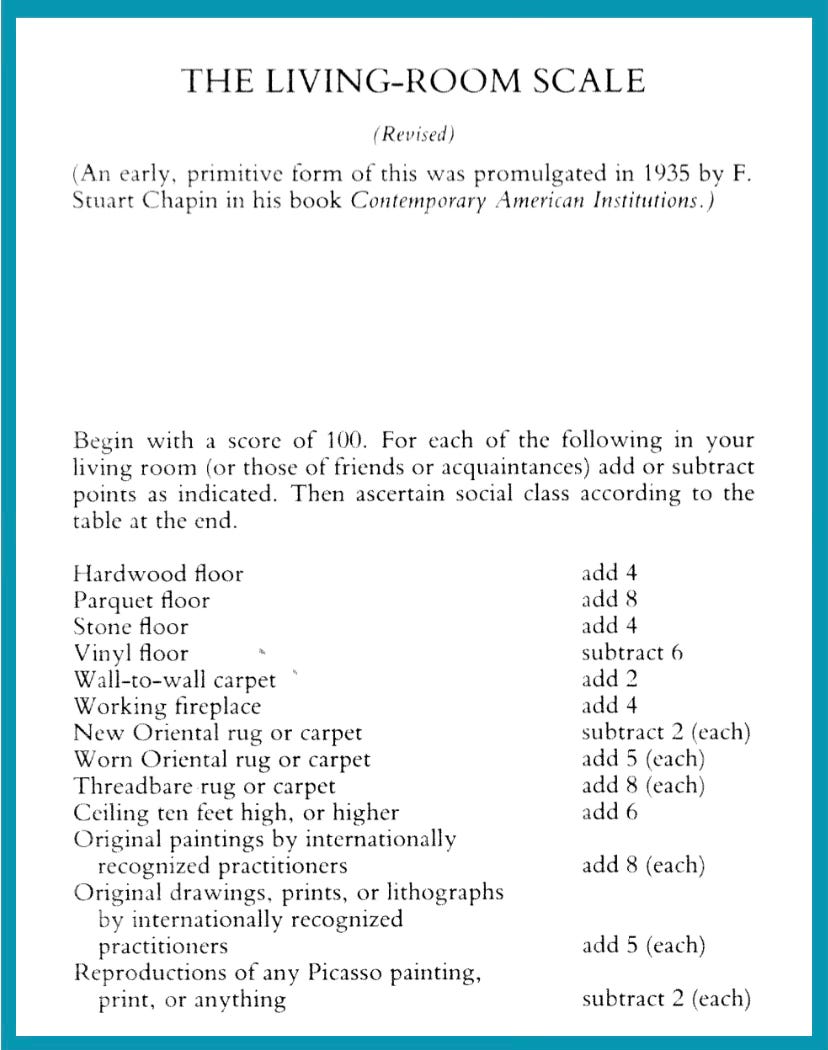

Click here for the other 2/3 of the scale and the scoring system.

I'd love it if my son's school banned phones, but also I'm not sure it would matter: Every kid has an iPad instead of textbooks. Which would make a ban pointless.

At home, we instituted a rule a few months ago: When he's in the house, he has to leave his phone on the kitchen table. Unused. He can use it when he leaves the house. He can use his iPad to do homework *in the living room.* But for pure messing around purposes? Nah.

It's not a death penalty for the phone. He can reach us - and us him - when he's left the house, which is often useful. But the time he spends at home is a heck of a lot nicer now: He doesn't disappear to his room to scroll through memes for hours. He'll come hang out with us more, and more time is spent in books. He still listens to podcasts, still texts his friends - but he generally does that when he takes his long walks. (He's obsessive about his step count, which would be the case whether he had a phone or not.) The "phone on the table" policy was initially a punishment; it's now policy, because it makes our collective family life a lot more balanced.

Now I just need to spend less of my free time screwing around on the internet.

Love Johnathan Haidt’s work and can’t wait to read this new book. I have been following some of the work he has been doing with Jean Twenge as well. I did read a few months ago that some schools in the UK had meetings with parents and in total agreements - the schools and parents decided to ban phones from 8am -3pm or so but it took immense work and a trust between the parents and school leadership. I don’t actually see that ever happening in American schools. Most parents I know from our little town of 80k love our school, but would much rather have their students have access to cell phones/smart watches or at the very least iMessage enabled on their iPads. Our family experimented with this a few years ago- when our child was in 8th grade we took away his phone for a month becuase of some bad choices he made and told him he could use the land line to connect with friends. It was probably the most lonely we had ever seen him. Not one friend called/texted/came to visit - this was over the summer break. Despite my efforts to pass on our number to the adults no one connected. We finally gave back the phone in two weeks and life came back to “normal” - what I find even more intriguing is that the majority of my friends don’t want to connect face to face or even have a phone chat - the would prefer texting or connecting via social media- I think we need to dig deeper and research - are we are becoming a society that would rather communicate via a keyboard versus actual sounds coming out of our mouths! Why are we all so addicted to our phones? Are we headed for a weird future where holograms and texts take the place of embodied friendships?