Childcare is expensive because caring for children is expensive

Plus: evangelicals and authority, a good sub, and more

Good morning! It’s Wednesday, and here are this week’s five items for you.

1. A take I haven’t written elsewhere

Childcare is expensive because caring for children is expensive

Several years ago, an editor at Reason reached out to me about writing on early childcare costs. Daycare is a steep bill for middle-class families, she observed. Could there be an unreported regulatory story there? Are the costs so high because of something stupid the government is doing?

I was intrigued and did a little cursory research, sure that instinct would prove correct. And while there are some ways in which unnecessary and onerous regulations are a factor,1 ultimately I had to go back to the editor and say I couldn’t honestly write the piece we’d envisioned. Big picture, I concluded, early childcare is costly because … early childcare is costly.

I tell this story now because the why is daycare so expensive when daycare workers are so poorly paid? conversation is going around my Twitter circles, and this strikes me as a good occasion to share the napkin math that led me to decline that commission as originally conceived.

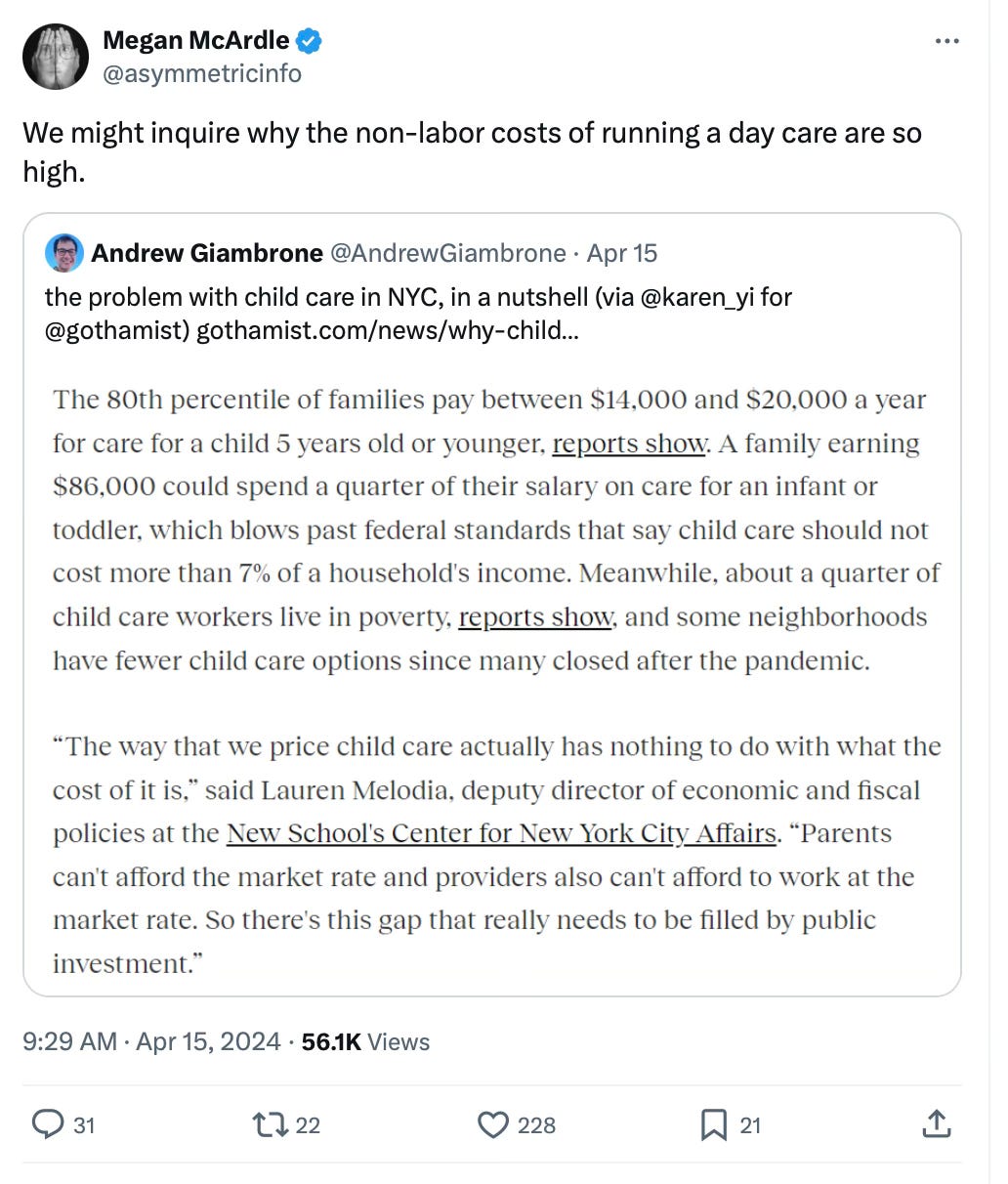

Here’s the tweet that came to my attention, and here’s the Gothamist piece it screenshots:

McArdle is a Washington Post columnist whose work I appreciate, and though she didn’t explicitly name the government as the likely culprit, her comment suggested her thinking was running along the same lines as my canceled Reason commission.

That’s where the Gothamist story goes, incidentally, albeit in a mirrored way. While I (and maybe McArdle) would love to say high care costs are the government’s fault for meddling in the market too much, the Gothamist article concludes it’s the government’s fault for meddling in the market too little. New York City childcare is too expensive, it argues, because the government doesn’t subsidize it enough.

That’s true, I suppose, in the bare sense that we could lower the sticker price on literally anything if we threw enough public money at it. But that answer doesn’t address the more interesting matter of why the sticker price is what it is—and why so many Americans are so sure something has gone wrong in the numbers.

Now, on to the napkin math. Let’s say you’re looking for daycare for a baby. In my state, Pennsylvania, one daycare staffer is legally permitted to watch up to four babies. For young toddlers, the ratio goes up to 5:1 and for older toddlers 6:1, but let’s stick to babies. This 4:1 ratio is a pretty standard arrangement at an American daycare; many states and municipalities have similar laws, and even if they didn’t, how many other babies do you want your baby to have to compete with for a caregiver’s attention?

Let’s say we’re going to pay the caregiver $20 an hour, which at full-time is $40,000 a year—not minimum wage in most of America, certainly, but nothing extravagant for the person with whom you’re entrusting with the life, health, and development of your baby for a full quarter of her first year. (For the sake of simplicity, we’ll imagine that these four babies’ parents all work exactly the same schedule and have no commute time, so we don’t need to allot more than 40 hours or bring on a second staffer.)

If this is a formal daycare center and the worker gets benefits like vacation time and health insurance, that can add another 50 percent in costs, so now we’re at $60,000 for the year. Don’t forget, we still need to cover taxes (employers pay 7.5 percent on Social Security and Medicare, which here works out to $3,000), facility costs, and administrative overhead including business insurance—and that’s before the daycare owner sees a dime of profit.

Very conservatively, let’s call it $80,000 a year for these four babies, of which $63,000 is spent directly on the one staffer’s wages, benefits, and taxes. Divide that $80,000 by four families for four babies and we’re at $20,000 a year.

Per the Gothamist story, the average annual cost to put your infant in a daycare center in New York is almost exactly that: $20,176. For toddlers, Gothamist says the NYC average drops to $16,900. This is basically the same cost split five ways instead of four, because now the children have aged into a 5:1 ratio.

You can see that the margins here are very, very thin. Just $17,000 to cover facility, administration, and profit. Honestly, in New York, I’d be surprised if there’s any profit at this rate. And while facility and administration costs may benefit from economies of scale, the biggest cost—labor—is basically fixed because of the ratios.

Now, if $20,000 a year seems hefty, there are two main ways to get costs down. One is to pay the staffer less. Maybe drop the wage and/or cut benefits. “The median full-time childcare worker in New York City earns only $25,700” a year, says a report Gothamist cited, which is a bit under $13 an hour. This is appalling, but suppose that’s what you pay. You might be able to drop the per-family cost by a third or more, especially if you live in a lower-cost area that is not NYC, by sticking it to the person with whom your baby spends 40 hours a week.

The other option is to increase the ratio. I’ve read that this is how other countries do it, including some countries in Western Europe that enjoy a very pro-childcare reputation in America. On principle, yes, I’d prefer the ratio decision be left to private decision-makers. But in practice, I think this is a case where state regulations and American parents’ preferences rightfully align.

There is no scenario in which I’d leave my infant in a 5:1 or 6:1 daycare arrangement. These ratios are fine for an hour of church nursery, but for eight-hour stretches amounting to nearly half a baby’s waking life? Even 4:1 strikes me as too much, frankly. We had twins, and I felt like I was drowning whenever I cared for both of them solo, a 2:1 ratio.

All that to say, McArdle suggested we “inquire why the non-labor costs of running a day care are so high,” but this math strongly suggests to me that labor costs generally will be the biggest expense and cannot cease to be the biggest expense because of how babies are.

The final question, then, is why it feels like the numbers must be wrong somehow—why early childcare feels “so expensive” even though it takes no particular expertise to run this math. The cultural explanation is straightforward, I think: We took it for granted when women in our families did the childcare for “free,” and indeed we called it “free” though it was always intensive, expensive work. We could ignore that reality when it didn’t have a sticker price.

Early childcare only feels unduly expensive now because we haven’t yet realized that it’s not “wrong” if daily care for small kids, particularly babies, costs as much as or more than a mortgage. Daycare doesn’t cost $20,000 a year because someone is making the big bucks. No one is scamming you. It’s just hard work to take care of little kids, and it’s costly to do it well. Perhaps eventually we will cease to be surprised that good care for children in crucial formative years doesn’t come cheap.

2. What I'm reading this week

Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism, by Molly Worthen. I’m only a chapter deep so far, but I’m already sure it’ll pop up in something I’m writing soon. That said, it’s not yet clear whether she’ll address pastoral authority (as opposed to intellectual authority), which is a topic that interests me right now. If you have any book or article recs on that, send them along!

3. A recommendation

This is very niche and will not help the vast majority of you, but if you live in West Michigan—I was just in Grand Rapids for the Festival of Faith & Writing last week—may I advise you to visit a location of Tallarico’s Boardwalk Subs? Make sure you get it “rogue” style; they do some magic with what appeared to be a panini press.

I love a good sub and have been disappointed with the sub scene here in Pittsburgh. It’s hard to find a place with truly spicy peppers, let alone a mixed giardiniera and good olives or artichoke hearts. While a few local places (Primo Hoagies and Peppi’s) are adequate, they’re nothing like The Italian Store in Arlington. Boardwalk Subs was quite a different style from The Italian Store, but it was the best sub I’ve had in years.

4. Recent work

3 better approaches to Beijing | Defense Priorities (newsletter)

5. Miscellaneous

Via

, this is almost unbelievable. City population, for context, is around 570,000.Read more from The Baltimore Sun—and if you doubt the 2,000 figure, here’s another local outlet reporting a very similar drop from “a quarter of 1 million Catholics in the city of Baltimore [to] somewhere between 5,000 and 8,000 Catholics participating on Sundays,” per a bishop. A bit better, but hardly, and perhaps that’s the pre-COVID figure mentioned in the second tweet.

Possible regulatory factors include:

As I wrote for The Daily Beast in 2022, Washington, D.C. has mandated college degrees for childcare workers. This is unnecessary and will only exacerbate the city’s already high daycare costs. The court decision that inspired this piece came well after the conversation with Reason, so this factor wasn’t on my radar then, but also, the mandate doesn’t seem to be widely imitated (so far).

Facility regulations do increase costs. In most cases, I think this is an instance of law and parental preference aligning, but I’m sure there are exceptions. Here, for example, are childcare facility requirements for North Carolina, which I believe to be pretty typical. They require an “adequate outdoor play area,” with adequacy to be determined by rules “related to the size of center and the availability and location of outside land area.” It’s possible to imagine such rules requiring an on-site playground when the children could simply use a public park down the street.

Similarly, a reply to McArdle said that New York requires daycares be on the ground floor for fire safety and that ground floor rents are often the most expensive.

We could probably add to this list, especially in the largest cities, but you get the gist. The regulations aren’t nothing; the non-labor costs aren’t nothing; but what I’ll argue is that labor is necessarily the main thing.

Excellent analysis. I'm troubled by the entitlement I hear in calls for "universal daycare", and how it's framed as a requirement for female empowerment / feminism. The majority of daycare workers are grossly underpaid, as you note, but they are also disproportionately likely to be immigrants from poorer countries. It strikes me as deeply screwed up to out-source caring for your children on less privileged and exploited women ... I realize it's not financially feasible in many cases for families to have a stay at home parent, I'm lucky to have been able to make that choice, so not trying to "shame" anyone, just lamenting the situation. Studies find a majority of mothers would choose not to work or only work part-time when they have young children, if they could afford to. If a government investment were to go anywhere, I wish it would go to helping mothers (or fathers) be able to afford to stay home with their children.

If you haven't read it already, you might find this essay by Laura Wiley Haynes on the negative impact of daycare on babies / toddlers interesting -- https://wesleyyang.substack.com/p/universal-early-childhood-daycare. Erica Komisar also has good work on this.

Glad this popped up in my feed so I could follow you here! I read your review of Abigail Shrier's "Bad Therapy" a while ago and was relieved that SOMEONE ELSE noticed how sloppy, misleading, and questionable many of the citations and research were in that book. (I also wrote a review pointing this stuff out, and other problems, and mentioned yours in mine a couple of times -- https://thecassandracomplex.substack.com/p/bad-journalism).

Great breakdown of the costs of providing care for very young children. I think the larger problem is that daycare just doesn’t scale. For every four infants, you need one full time adult worker who is willing to take care of four infants. I am pro-baby all the way—they are great—and I loved my own babies more than life itself, and I was lucky enough to be at home with them for their first years. When I was an at home mom I participated in a babysitting co-op and a co-op preschool—both really cost effective ways of getting occasional child care. Taking care of other people’s children is a slog. Minutes seem like hours. A two or three hour stint felt like a lifetime. Not everybody feels this way, but be honest—how many people in this world are willing to take care of other people’s kids 40 hours a week?

The best thing the government could do is to give money to parents so that they can either use it to purchase child care, or use it to cut back on work and raise their kids. If you are in the top 20% or so of wage earners, you probably have a pretty interesting career and it makes sense to keep doing what you are doing and hire out child care while you do research or invent things or heal the sick. If you are the parts manager at an auto dealership, maybe raising your own kids for a few years is the more interesting and rewarding path. Not every job is a calling, and raising your own children and being part of a community of other parents is rewarding and has other social benefits.

I’d be curious to see good quality research on the costs over a lifetime of taking 5-10 years off and then going back into the workforce. If they expect people to work until they are 70, why not subsidize a break for parents so that they can take care of their kids for a few years?