We should think more deliberately about risk assessment

Plus: Eschatology and politics, abandoned castles, and more

Good morning! It’s Wednesday, and here are this week’s five items for you.

1. A take I haven’t written elsewhere

We should think more deliberately about risk assessment

Over at The Bulwark,

, with whom I worked a bit at The Week, has perhaps the sole unique angle on January’s gas stoves kerfuffle—and that’s because it’s mostly not about stoves at all. As his headline says, it’s about “What the weird clash over gas stoves tells us about conservatives and risk.”I’ve written on different risk assessments a handful of times, at least once at The Week (“Why pandemic parenting is harder than the data suggests it should be”) and more recently at Reason (“Left and right are living in different realities”)—maybe enough that I’m straining the bounds of this item category. But I’m coming back to the topic because I find it fascinating. (And, eh, my Substack, my call.)

Risk assessment is something we often do subconsciously and usually notice, if we notice if it at all, at the individual level—you know: My husband is so cautious; he takes forever to make a decision with any big purchase or Yeah, she just moved there without knowing anyone! I could never. Even then, we don’t necessarily make the leap to thinking about risk assessment on a societal scale or as influenced by politics or religion or other factors beyond individual personality.

This has all sorts of deleterious effects in politics, because one man’s unspeakably reasonable via media is another’s safetyism and a third’s recklessness. Failing to explicitly examine our personal risk assessments can also lead to inconsistencies within our own decision pool, as Addison explains:

Cooking entails risk; if you do it wrong, you could burn yourself or get food poisoning. Yet driving to the restaurant also entails risk; you could have a car accident. Gas stoves entail some health risks, yet if you find a gas stove to be the only usable type, perhaps your overall health will be improved by cooking at home with gas versus eating more unhealthy takeout food. Etc., etc.: Everything involves risks, and so acknowledging and weighing them is unavoidable.

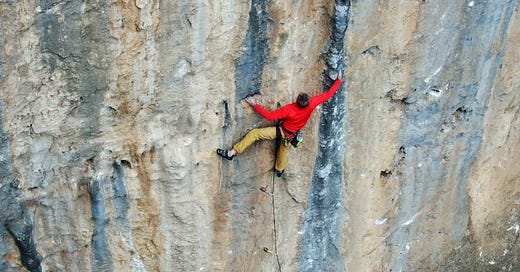

But those conservatives who speak in high-minded abstractions [about risk] seem to be driving at something more than this mundane observation. One often gets the sense that they believe that risk is not just inevitable, but somehow good; that is it invigorating; and that attempting to eliminate risk is not merely futile but cowardly and enervating. One wonders, in fact, if they can tell the difference between risks inherent in the business of living and risks that arise from specific and remediable actions or inactions.

But once again, slipping into culture war mode means that none of this can be weighed and considered. And so we’re faced with the odd sight of people who would do anything for their children, like move to the safest possible neighborhood with the best possible schools, scoffing at the idea that keeping a gun in the house, or running a gas stove, could possibly present any risk at all.

You can’t “determine your risk tolerance if you cannot even acknowledge a risk,” he concludes, and to that I’d add: You can’t understand other people’s risk assessments if you can’t think deliberately about your own and come to understand why your perception of risk may or may not correspond with reality.

2. What I'm reading this week

From New Testament scholar

, the above except of his forthcoming book, Revelation for the Rest of Us: A Prophetic Call to Follow Jesus as a Dissident Disciple, which is going on my to-read list.I’m increasingly interested in how Christians’ end times theology affects our politics—I’ll be reviewing another forthcoming book on the subject, The Rise and Fall of Dispensationalism, for Christianity Today, and I’ve got an article in the works right now on related topics.

A big part of my interest stems from the fact that most people paying attention to eschatology and politics seem to do so in the “speculative, dispensational” style McKnight critiques. That is, they’re eagerly reading Revelation into the headlines and vice versa, maybe going so far as to speculate that X might be the antichrist or Y is a sign of the times. Those who don’t take that approach seem to average a lower level of interest in eschatology generally, which means the conversation is dominated by just the one model. Maybe McKnight’s book will begin to change that balance.

3. A recommendation

Reddit’s r/abandonedporn and r/reclaimedbynature, plus tags like #forgottenplaces on Instagram. As you’ll guess from those names, the content is photos of buildings and other human constructions which have been abandoned to various states of decay. My favorite are the abandoned castles, many of them remarkably undisturbed despite decades of disuse, left as time capsules of the 1930s or 60s—I like to try to figure out the decade from the items left behind (and often have deep envy of the furnishings).

4. Recent work

America’s brash grandiosity | Christianity Today, in collaboration with

's Center for Christianity and Public Life and the U.K.-based org Faith in PublicIf China invades, Taiwan shouldn’t count on U.S. support | Reason

Today is the release day for the tech ethics book to which I contributed a chapter! It’s called The Digital Public Square: Christian Ethics in a Technological Society, and you can buy it straight from the publisher, at Amazon, or via local bookstores like Hearts & Minds.

My chapter is on proposals to ban online porn (and other objectionable content), thinking through the legal and practical viability and teasing out some aspects I too often see ignored in this debate, like how we’d propose to punish offenders and what bans do to the human moderators asked to enforce them.

Untrustworthy, of course, also remains available for purchase straight from the publisher (30% off!), at Amazon, or wherever you get your books. And if you can’t spring for it right now, your library will almost certainly buy a copy if you ask.

5. Miscellaneous

I’m neither very rich, Lutheran, nor a paedobaptist, but the core idea here is intriguing and something any wealthy Christian could do for any congregation (tie it to baby dedications if you don’t baptize babies):

Click through to the rest of the thread to see his reasoning and box content ideas.